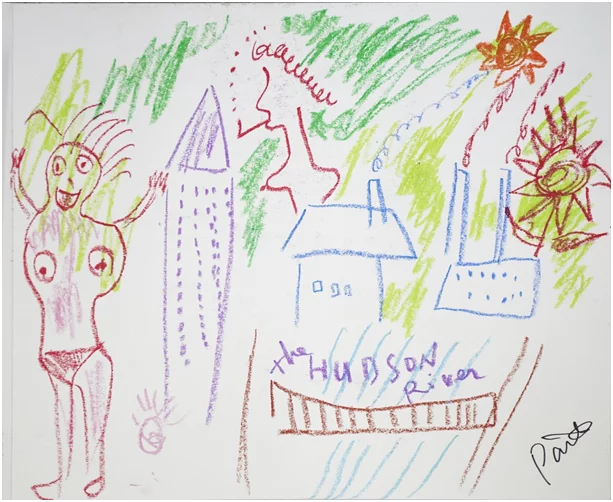

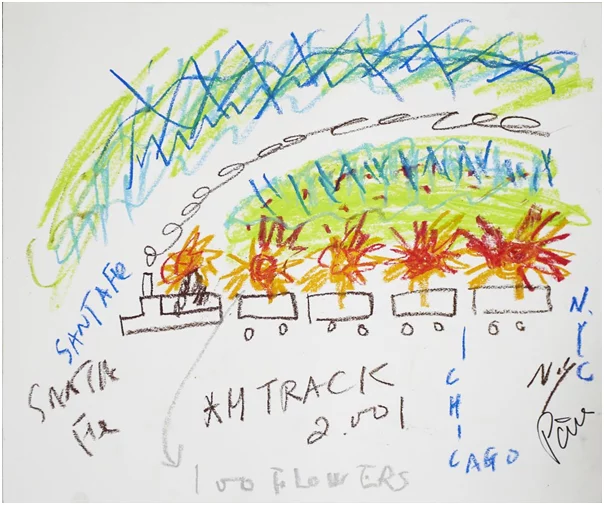

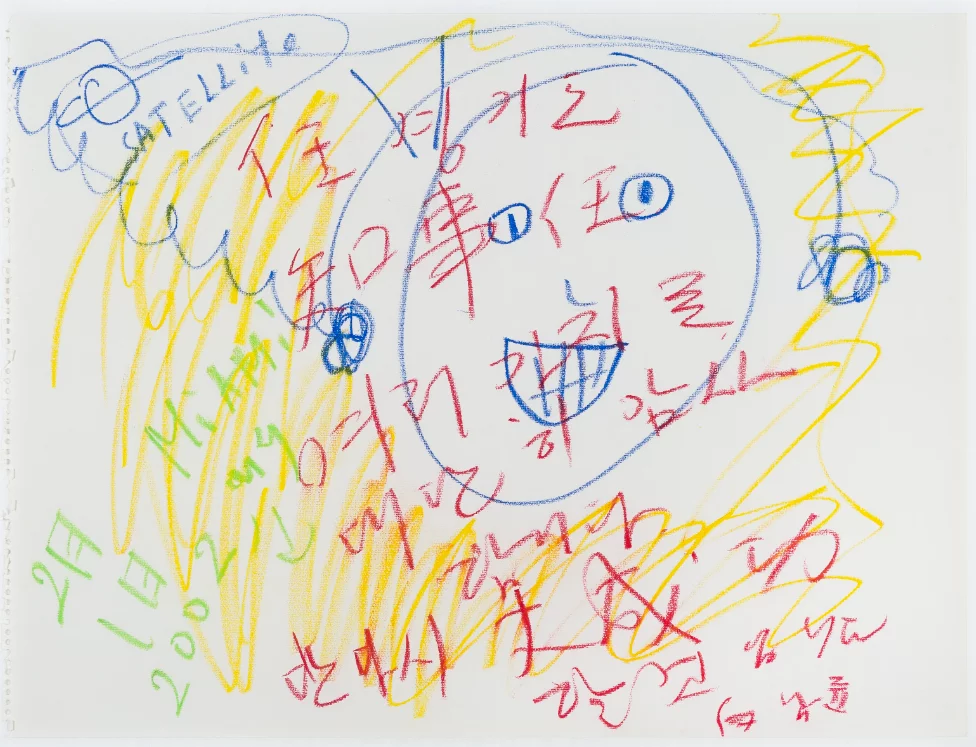

Nam June Paik left behind various documents in different languages, including letters, scores, essays, proposals, and reports. One of these, a 1974 report somewhat grandly titled “MEDIA PLANNING FOR THE POST INDUSTRIAL AGE: Only 26 years left until the 21st Century,” seems more like a policy research document than an artist’s note. Instead of simply sharing bold ambitions, the report contains detailed and concrete plans for implementation. The text shares a vision akin to what has been realized today with the internet, stressing the urgency of being able to transmit ideas in real time through “electronic super highway,” just as the building of highways in the 1930s had enabled the movement of goods and the achievement of an economic revival. Emphasizing that “Mind pollution is as bad as air pollution,” Paik also urges caution in ensuring that media communications are not monopolized by technology experts or some “mysterious power complex.”

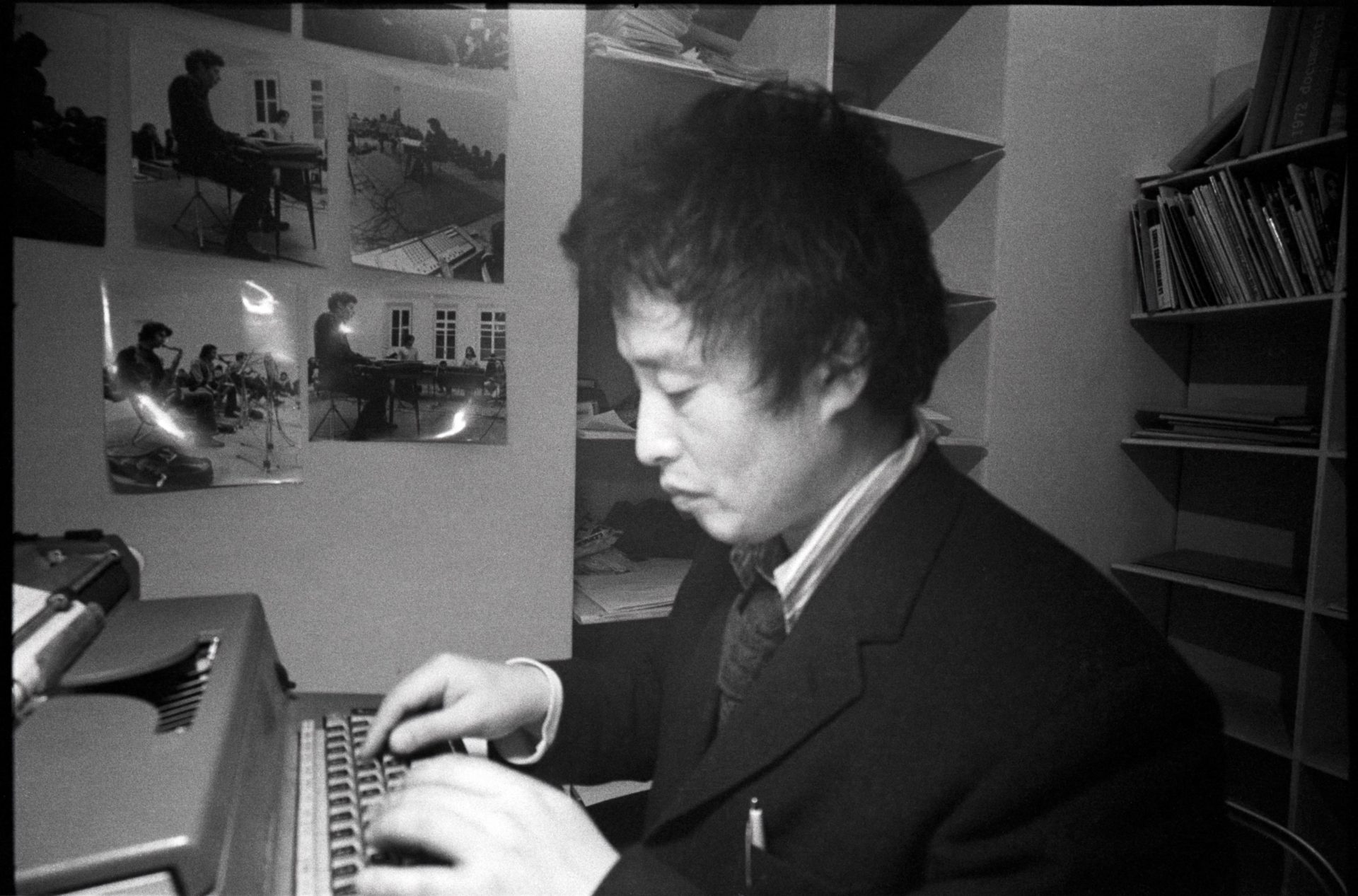

Paik actually did carry the title of “consultant.” While he was based in New York, he carried out his work with Rockefeller Foundation Art Grants in “Television/Video/Film” and for a roughly 20-year period beginning in the mid-1960s, he served in ofcial and unofcial advisory roles, playing a leading part in emphasizing the importance of supporting medial eld and proposing directions for its development. During this time, his video art and the video community were broadcast on television channels, discussed in scholarly contexts, and exhibited, collected, and proliferated by art institutions. His proposal expressed his bold ambitions of solving social problems through the medium of art, with immediate implementation plans laid out in considerable detail: digitalization to record and preserve human cultural history, video exchanges as a tool for learning and resolving our lack of understanding toward different cultures, the creation of electronic superhighways as communication systems connecting the world, and the continued pursuit of diverse representation in public broadcasting content.

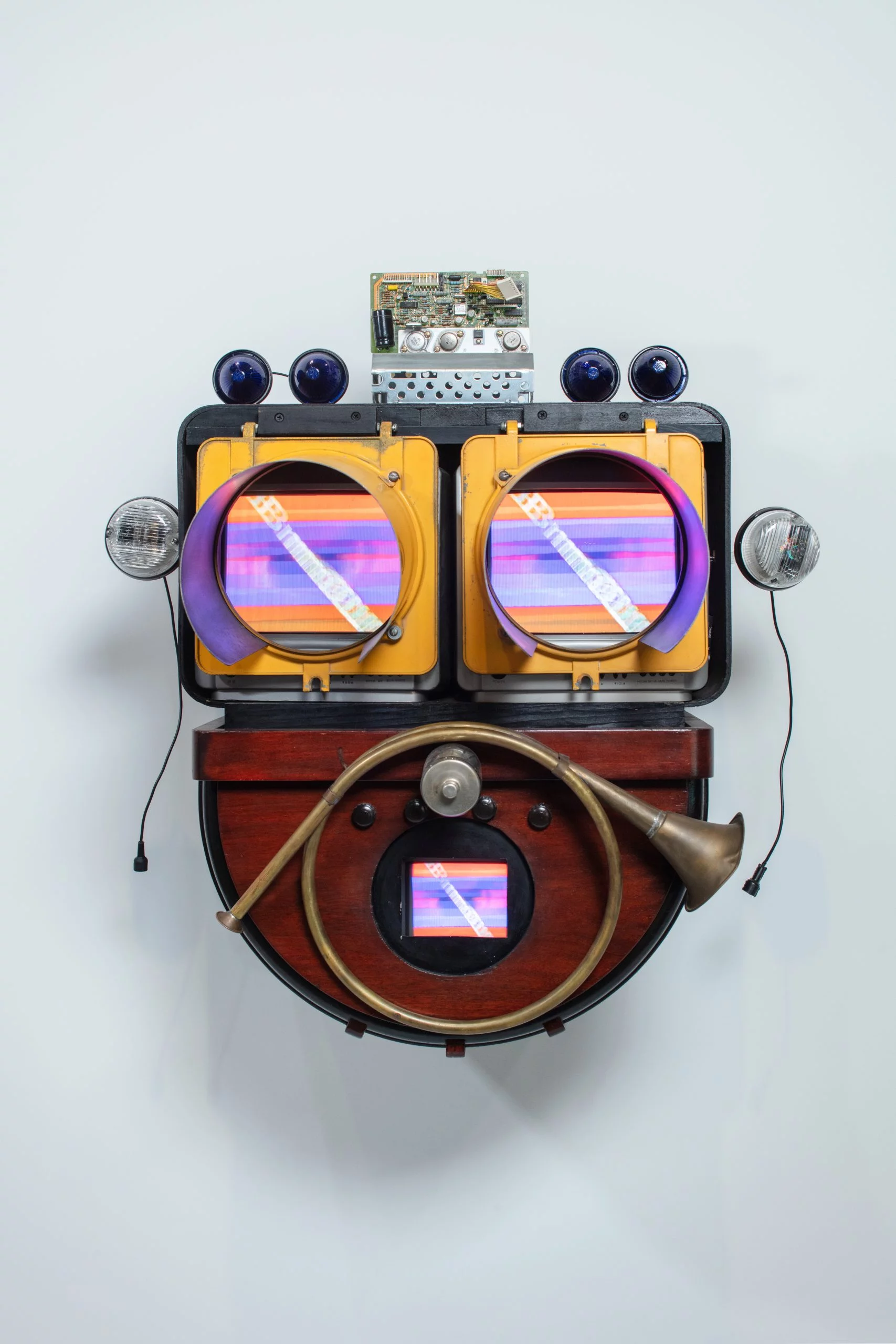

As its title suggests, The Consultant: Paik‘s Papers 1968–1979, a special exhibition commemorating the 90th anniversary of Paik’s birth, takes the artist’s reports as its starting point. Rather than emphasizing his individual achievements and the aesthetic context for his video art, it considers Paik as a“policymaker” based on three reports that he wrote in English between 1968 and 1979: “EXPANDED EDUCATION FOR THE PAPERLESS SOCIETY” (1968), “MEDIA PLANNING FOR THE POST INDUSTRIAL AGE” (1974), and “HOW TO KEEP EXPERIMENTAL VIDEO ON PBS NATIONAL PROGRAMMING” (1979). Compared with his achievements focusing for a lifetime on the medium of video art, relatively little is known of how Paik investigated the raisons d’e^tre for social infrastructure and art and suggested new avenues for them. As it examines his work through the lens of Paik’s papers, the exhibition urges the viewer to seePaik in a new light, while showing how the realization of his artistic vision was underpinned not only by institutional support from the government, but also by collaboration with and support from private foundations, patronage funds, public schools, laboratories, broadcasters and art institutions.

The exhibition’s aims lie in taking a detour from the historic highway of regarding Paik as the “father of video art” and seeing him in a different light on a different sort of path—leaving behind the crossroads of preexisting knowledge and experience to nd new opportunities for liberation. Exploring Nam June Paik as an analyst, a media consultant, and an agent of change for social infrastructure and technology during the social transitional period of the 1960s is a way of uncovering new tasks that have heretofore received little attention in studies of the artist, while also creating new points of contact with his works of electronic art. As we stand amid a different kind of digital shift and social change today, Paik’s media consulting is a work that is still in progress.