Oh Jooyoung is an artist as well as a researcher working on artificial cognitive models. Her two interdisciplinary areas are visual design and engineering. From the perspective of a scholar she has studied simulations of artificial cognitive models with an interest in the human visual cognitive process. Also, from the viewpoint of an artist she constantly questions the limitations of scientific technology. The artist is interested in exploring the identity of individuals and ways of thinking, particularly using a scientific methodology that is considered to deal with the most objective facts.

1. Please introduce yourself and your work.

I am a media artist using interactive technologies such as games and artificial intelligence chatbots. I have developed my work under the interdisciplinary background: visual design and engineering. Interested in the human visual perception, I conduct research on the simulation of artificial cognitive models, and at the same time constantly ask questions about the limitations of science and technology from the artist’s perspective. In 2017, I received the Grand Prize of ART+SCIENCE COLLIDE (organized by Daejeon Artience and hosted by British Council) for Aging Brain. I produced BirthMark while an artist-in-residence at ACC Gwangju in 2018. I also took part in the ISEA 2019 International Exhibition Division, and in the Da Vinci Creative Exhibition in 2018. In 2019, I received the IEEE BRAIN WINNER Award from Ars Electronica (Austria, Linz), and the first place of the Korea Creative Content Agency’s contest for the interactive work CURVEilance, and participated in the KOCCA’s exhibition IMPACT X twice. In 2020, my work was included in NEURAL.IT, a renowned Italian magazine of media art. I continue to participate in various competitions and exhibitions in Korea such as Nam June Paik Art Center and Ilmin Museum of Art.

At the beginning of my career as an artist, I mainly worked on photography. My debut was a photographic solo exhibition, and it was a monthly photo magazine that first introduced my work. As I took pictures, I studied its technical implications and human visual perceptions, and started this technology-based work with a program that distorts a series of processes in which photos are taken, shared, and appreciated online. The first work of media art was called Profiled by Profile, and while working on a photographic machine at a closed factory in Munrae, I expanded the questions of visuality to scientific and technical concepts. What followed was Aging Brain, a game that visualizes the cognitive changes where you can see and feel the process of aging. This work was selected as a winner at ART+SCIENCE COLLIDE, which gave an impetus to my pursuit of science-based art in earnest. I then used the artificial intelligence model, which was the subject of my doctoral research, differently from the purpose of the study, and for two years created a work of artificial intelligence that could not enjoy human-like appreciation of art. In a way, it was contradictory from the researcher’s point of view, because after making it into a scientific program, I denied it. Coincidentally, it was in 2018 when the expectations for the possibility of artificial intelligence was being heightened after the announcement of AlphaGo, so I ended up throwing a message that reversed the times. Fortunately, this was accepted positively, so I was selected by such institutions as Pyo Gallery, Seoul Arts Foundation, and the exhibition Goldfish by Contemporary Art Society, Hongik University. This work was also included in the international exhibition of the ISEA 2019 competition and in SIGGRAPH ASIA 2020, the world’s largest graphics journal.

In the works afterwards, I brought the technological imagination back to the past, raising a question as to when humans became passive in machine-led developments. It was based on scientific facts obtained from various pilot tests of the artificial cognitive model under my study at that time. As I realized that the technology of automation developed especially in the situation such as World Wars, I was obsessed with a strange feeling of déjà vu. My main research interest was to identify the hidden context and origin of technologies that often leave behind people and stories. This work is With Blind Landing, selected for Da Vinci Creative 2018 by the Seoul Foundation for Arts and Culture, and showcased in 2019. I intended to show the dangerous side of technology when we follow someone’s instructions or judgments rather than our own senses. This work analyzes the predictability of gaze on a real-time basis by artificial intelligence connected to an EEG meter in an old aviator’s helmet with a gaze tracker. Thanks to several international curators who found this work interesting, it was published in NEURAL.IT in February 2020.

2. How did you find it to take part in the project Random Access?

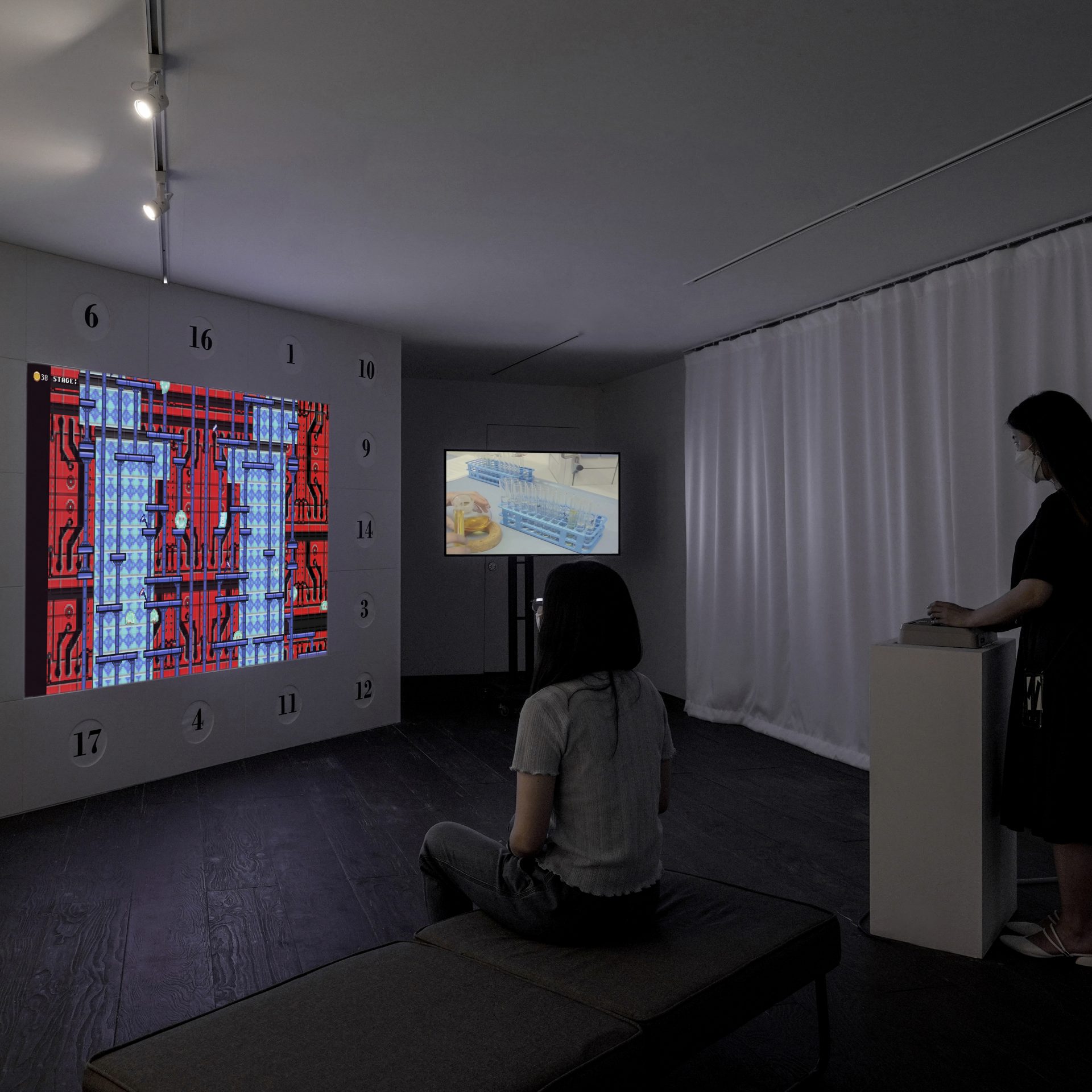

I think that I have grown up as an artist through Random Access in the sense that I made new attempts in the communication with the audience. It was also challenging but fun in dealing with the space. For those who do not know the space, the exhibitions of Random Access take place in the Eum-Space of Nam June Paik Art Center. It is a container box for export laid horizontally in the backyard. The form looks like a shipping container that crash-landed in Paik’s place, yet reveals a strong presence. It seems like an in-between space, somewhere inside and outside the institutional sphere. After several days of contemplating how to create an immersive environment in the space, narrower than expected, I made the work in the form of a game at the suggestion of curator Jung Yunhoe. For the whole exhibition, I was most concerned with how to draw out my message to the audience’s participation and immersion. My work is mostly experiential, and as with contemporary art, it is difficult to give the audience a proper viewing experience, without additional explanation. The proposed online game came to light particularly when all exhibitions were closed due to the covid-19 pandemic, with my exhibition open to public only for two weeks too.

3. Your practices are quite interdisciplinary, borne out of visual design and engineering. In your work, there seem constant efforts to break out of the fixed genres of art, and to break the boundaries between the artist and the audience. I think these are in a way in line with what we can see in Paik’s work. Which part of your work do you think is personally or artistically connected to Paik?

Paik’s work serves as a model for many artists. I think that we can find out in his world of art, from the notion of art expanded, to the boldness of expression. With photographic technology I tried to transform the relationship between art and its audience through engineering attempts, which might be in the same vein as Paik’s television. Now we take, produce, upload, and consume photos and video images with a variety of smart devices. Our visual environment is made up of lighter and smaller devices than the television of Paik’s days, which we can control or we believe we can. It seems that the creative process of appropriating what is hidden in smart devices and making it into art is the revolutionary quality shared by me and Paik, if I dare say. If I had become an engineering developer, my work would have been a big problem, like an angular stone bound to be hit by a chisel. But as an artist, you can happily get into trouble.

Paik’s experimentation much surpassed the existing technological scope and foresaw the future insightfully, whereas I am paying attention to what is being repeated by returning to history, rather than predicting what comes next. This is the reason why I majored in engineering again after graduating from the art college. I need to know the inner workings to understand what is constructed and how. The media I make use of always conceal new technologies under the surface of old things from the past. I put the 70s Soviet helmets on the latest EEG medical devices, or create an Ai program (developed in 1970) and project the core data of the operating system to the old lanterns of the 60s and 70s. I am a bit pessimist in that the reality we live in is still stricken with the illusion of technology such as AI, network, biotechnology, and that it will not always lead us to the ending we wish for. Perhaps I might want to disclose that the future predicted by the past is being stagnant. It contains my rejection or regret that I would rather not discover anything new. Where the illusion disappears are questions about the past instead of blueprints for the future. Where do we have to go to reach “that” future? In my opinion the underlying philosophy of tech people seems to be the same as before.

4. Tell us more about Hope for the Rats and BirthMark showcased in the exhibition Dice Game for Random Access.

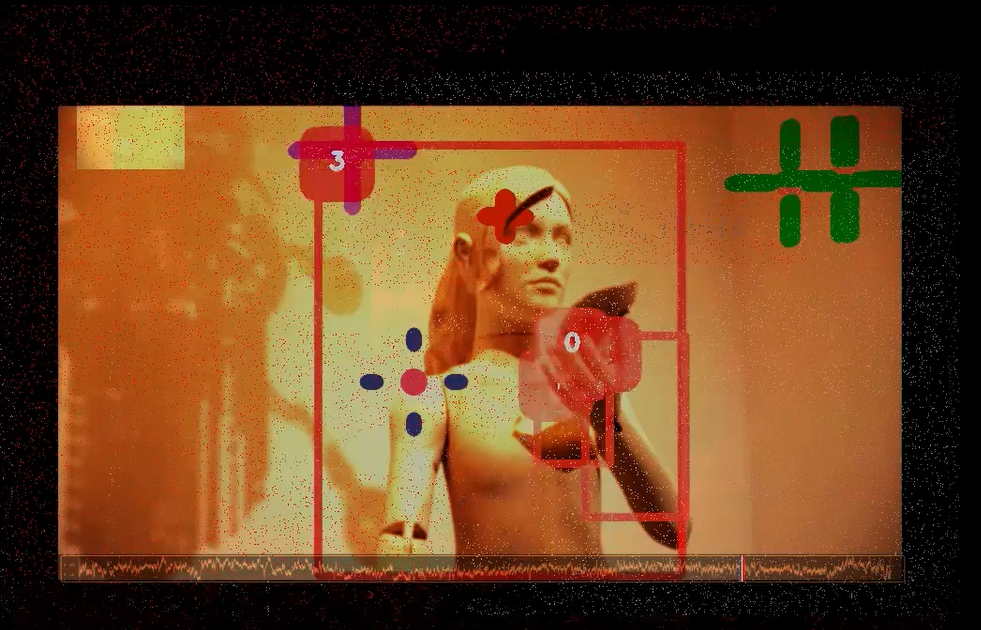

Hope for the Rats is a video game where you become a rat for experimentation and experience the researcher P’s failures. You are invited to become the subjects of researcher P by the process of going through symbolically implemented stages while manipulating laboratory rats in the game. You will experience the difficulties in discovering truths and the ensuing sacrifices. Repeated failures that you are bound to experience during the course of playing the game are reminiscent of the imperfect basis on which scientific truths are founded.

The contemporary life is surrounded by the outcomes of numerous scientific studies, but it is virtually impossible for the public to deeply understand the diverse and complex scientific achievements. Based on my own experience as an artist and researcher, the exhibition Dice Game showed that the foundation on which scientific truths stand is not as strong as our expectations. Sometimes research and experiment of scientists are repetitively conducted inevitably out of hope and a sense of responsibility. I wanted to pay attention to what was concealed in it, and whether it was considered replaceable. In a similar vein, BirthMark is a story about my research failures doing a Ph.D. As symbolized in the short story of the same title, it reveals that there are human areas that are difficult to explain with scientific methodology alone. BirthMark “appreciates” the works of different artists exhibited through the three-sided projection screen and the 70’s lantern screen, and the results of perceiving them are played on video. The information and processed data of the works are displayed in real time in conjunction with the small monitor of the old lantern. As if an eye blinks, each time the slide of the lantern is flipped over, another work enters the field of AI vision. The old lantern, which is suitable for the artificial cognitive model in use, is provided with a description how artificial intelligence understood the works semantically. The meanings analyzed by AI through this old lantern are only about 2-5 out of 300 words. The more abstract the work is, the more sharply the understanding of artificial intelligence decreases.

5. You have been active since Random Access. Could you tell us about the activities you have engaged and about your future plans?

Covid-19 turned severer after Random Access, but fortunately, I was able to continue to work. In October, I participated in the exhibition Unfold X at Seoul Art Space Geumcheon, as one of the artists for the Da Vinci Creative Biennale, and presented a work of game-type theater. Unlike its basic format, this theater does not give the audience an immersive experience. Rather, it is an open hexagonal structure that can be easily overlooked if you are not interested. In fact, one of my primary spatial motives was the columnar control room. This work began with the imagination of the near future where the audience could control the theater with easier interaction technology. The theater deals with the automated future that Ai will create.

First, Your Love is Fake as Mine is a video work about four different love stories created by AI based on romance novels. Themed with various meetings and separations, and eternal love, the story proceeds in the form of visual poem through the avatar who leads you to read a novel. This work came from the idea that if a huge amount of data on love was accumulated, the archetype of love could be understood with sophisticated statistics out of natural language processing. The resulting novel surprisingly excelled in depiction. All of the videos in the novel featured the faces of Ai who do not exist in this world put on those of the original characters. From the viewpoint of a producer, the sources of the Deepfake video were more interesting. Recently, as investment has decreased due to production costs in the film market, there are some filmmakers who have changed their business by creating short narrative videos instead of films. These videos are usually available if you pay royalties. I think there will be more in the future, and eventually, there will be more stories made by data than real stories, or those using avatars than living people. TVs showing romance novels as visual images are installed on hexagonal pillars like control towers. This video is attached as a front mirror and illuminates the audience throughout the reading of the novels provided by AI, but if the audience looking in the mirror turns their body slightly, they cannot see their bodies from anywhere. AI technology will accelerate automation and result in blind spots that the data cannot show. It is impossible to know what data is processed and how, and the more biased the data, the more ethical problems of the algorithm will be inevitably emerging. Hence the AI theater is a space that entices humans with a rosy future, but, at the same time poses the technology’s dangers.

The AI novel project has been developed into various versions by now. In a workshop with Slow Futures Lab, which plans to participate in the Venice Biennale next year, I worked through the Korea Creative Content Agency’s curriculum and presented a disaster novel generator co-creating dialogue through Ai who learns about the past novels. The developed version of this work was shown in the exhibition of the Ilmin Museum of Art, 1920 Memory Theater: The Gold Rush. Here, visitors have the fun of asking and answering questions in real time to AI Koobo, a person from the past. And for the exhibition Play on AI at Art Center Nabi, I showcased Your Love Counseling Bot by processing data in an anonymous conversation app about real love-related worries, breakups, and other very private stories. Even if the AI advises you as if he or she had the experience of loving someone, it comes out of merely a list of learned words. I wanted to show that the text written by AI who does not know love is false, and the emotions it arouses is a kind of false emotions toward humans created by machines.

The last one is my solo exhibition Let’s Know What I Don’t Know held in Place Mak, which I have been preparing for a year. Derived from the rat game showcased at Nam June Paik Art Center, two games, Hope for the Rats, Unexpected Scenery and three installation works, Virtual Environment Controller, BirthMark, Scientist’s Dice Game, and Blind Landing were on show. This exhibition, which is an extension of Nam June Paik Art Center’s Dice Game, brings the lives of researchers that have been veiled to the center stage of the exhibition. I was interested in the fact regardless of success or failure of scientific discoveries, we are ignorant of the direction that these repetitive activities lead us, and of the ways how these are transforming human lives and organisms.

6. Selected as a Random Access artist, you produced new works through consistent discussion with curators of Nam June Paik Art Center. Do you have any comments or episodes you would like to share about Random Access?

Hope for the Rats, commissioned by Nam June Paik Art Center, is a work that I devoted a lot of efforts to and spent a lot of time on. For this work, I invited a failed researcher, and based on her journal, I began by deeply sympathizing with her. Even in the whole process of making a game, her research was in an intermediate stage, so it was very difficult to conclude. I was thinking if it would end with a bright ending, but there are already so many bright stories. With Hope for the Rats, I intended to more consciously talk about what is not visible. What I have been paying attention to is not science but the process of research, which is the routine of most scientists. On the one hand, there were some concerns about only criticizing science in general, and I was also concerned too if my work might be misunderstood. Thankfully it received a lot of responses from the scientific community. It is what you would have thought about at least once if you did research, although for those who do not it is somewhat puzzling. Anyway, the game’s ending was a bit dark, but fortunately, the real character achieved a good result of her research. From the observer’s point of view, her research activities were very hard, but eventually it was rewarding. It is great news for me too, who created the work by borrowing part of her life. If the good result had been reflected in the work, the game might have been a little brighter. It would have been less fun then, though.